Sociodemographic characteristics and probabilities for the labor inclusion of people with disabilities in Chile. Implications for critical social policies

Características sociodemográficas y probabilidades de inclusión laboral de personas con discapacidad en Chile. Implicancias para las políticas sociales críticas

Fecha recepción: abril 2021 / fecha aceptación: mayo 2021

Carlos Andrade-Guzmán1, Javier Reyes-Martínez2 y Lorena Valencia-Gálvez3

DOI: https://doi.org/10.51188/rrts.num25.492

Abstract

In Chile, labor inclusion for people in the situation of disability is low. By using the Second National Survey of Disability in Chile and running a logistic regression model (N=2,618), this study explores how sex, education, age, and level of functional dependency are associated with the probability of people in the situation of disability of having work. Findings suggest that being a woman with a disability or being older reduces the probability of having work. Besides, having more years of education increases the probability of it. Implications for critical social policies are also discussed.

Keywords: People in the situation of disability; Labor inclusion; Sociodemographic characteristics, Implications, Critical social policies

Resumen

En Chile, la inclusión laboral de personas en situación de discapacidad es baja. Utilizando la Segunda Encuesta Nacional de Discapacidad de Chile y ejecutando un modelo de regresión logística (N = 2.618), este estudio explora cómo el sexo, la educación, la edad y el nivel de dependencia funcional se asocian con la probabilidad de que las personas en situación de discapacidad se inserten en el sistema laboral. Los hallazgos sugieren que ser mujer en situación de discapacidad o ser mayor reduce la probabilidad de tener trabajo. Además, tener más años de educación aumenta la probabilidad de que lo tenga. El trabajo presenta implicancias de los hallazgos para las políticas sociales críticas.

Palabras clave: Personas en situación de discapacidad, Inclusión laboral, Características sociodemográficas, Implicancias, Políticas sociales críticas

Introduction

In Chile, 20% of the adult population corresponds to people in a situation of disability (Servicio Nacional de la Discapacidad, 2016). This percentage represents more than 2,600,000 persons that are at risk of suffering poverty, and social exclusion (Martínez, 2011). Chilean State has developed different public policies over time to promote the labor inclusion of this group (Álvarez, 2012). Nevertheless, taking as a reference the total of the population who participates in remunerated works (employed), people with disabilities correspond to just 13.3% (Servicio Nacional de la Discapacidad, 2016), which represents a low percentage of people in this situation accessing the work system. Despite the relevance of this issue, little is known regarding how socio-demographic characteristics of the people in the situation of disability are connected to the probability of participating in the remunerated labor system. This study contributes to fulfilling this gap in knowledge.

Literature Review

In literature, there are several advances in knowledge regarding disability and employment. Some authors emphasize how employment has the potential to develop individuals’ activities, skills, and talents; increase their social capital (Silva et al., 2019); as well as improving life conditions (Ordóñez, 2011). Contrary, unemployment among people with disabilities has severe consequences on well-being, quality of life (Birau et al., 2019), and health (Gallegos, 2019).

Regarding employment gaps between people with a diagnosis connected to disability and those without it, several individual factors intersect. Some of the most referred in literature are gender (Barea & Monzón, 2008; Birau et al., 2019; Coleman et al., 2013; Garrido-Cumbrera & Chacón-García, 2018; Pereda et al., 2003), age (Birau et al., 2019; Coleman et al., 2013; Garrido-Cumbrera & Chacón-García, 2018; Pereda et al., 2003), type of disability (Barea & Monzón, 2008; Pereda et al., 2003), education (Barea & Monzón, 2008; Birau et al., 2019; Gallegos, 2019; Ordóñez, 2011; Pereda et al., 2003; Quiñones & Rodríguez, 2015; Silva et al., 2019), qualification (Coleman et al., 2013; Gallegos, 2019), poverty (Green & Vice, 2017), economic status (Birau et al., 2019; Quiñones & Rodríguez, 2015), participation in association or social groups (Barea & Monzón, 2008), and place of living (i.e., rurality) (Rodríguez, 2009).

In terms of barriers and obstacles for accessing a job in the disability field, previous literature has highlighted the role of stigma, discrimination (Garrido-Cumbrera & Chacón-García, 2018; Lindsay et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2019), and disinformation (Silva et al., 2019). Other contextual barriers in the literature are non-accessible workplaces, inappropriate public transit, and challenging training (Lindsay et al., 2018; Ordóñez, 2011), difficult of diagnosis, lack of figure of support at work (Ordóñez, 2011; Silva et al., 2019), and lack of knowledge in the organizations (Silva et al., 2019). The sum of these negative aspects generates occupational segregation and marginalization mechanisms that diminish the valorization of this group of people (Quiñones & Rodríguez, 2015). In the work inclusion of people with disabilities, the role of public policies, legislation, and normative implementation has also been observed as relevant (Birau et al., 2019; Pereda et al., 2003; Silva et al., 2019). For instance, social insertion via pensions versus via employment influences the level of unemployment (Pereda et al., 2003).

All of these studies represent approximations that allow recognizing that some socio-demographic elements like gender, disability condition, and others, can be related to the chance of having a job within the Chilean labor system. However, they do not provide concrete answers about which of these can be connected to have a higher or lower probability of having work. Besides, current research does not contribute to identifying the quantitative connection about these variables with the probability of having work, from a perspective that shed light regarding different directions that critical social policies can take to move forward to the active labor inclusion of people in the situation of disability in Chile.

Paradigmatic Position

The paradigmatic position of this study is critical (Guba & Lincoln, 2005; Pérez, 1994). It is based on our experiences regarding social policies and interventions. The first author is a Chilean social work researcher on human rights and disability with former experience in the intervention field of disability and dependence. The second author is a social welfare researcher on human rights and vulnerable populations. Finally, the third author is a social work researcher with experience in intervention with people in a situation of disability. We consider that people in a situation of disability are entitled to the right to labor. Thus, we advocate for generating the best conditions, so these individuals can exert their rights.

That being said, we understand disability as the result of the interaction between a specific diagnosis and environmental conditions (Convención Sobre Los Derechos de Las Personas Con Discapacidad (Español), 2006). Therefore, we understand disability based on a social perspective (Andrade-Guzmán et al., 2014; Martínez, 2011; Palacios, 2008). For us this means disability will be higher or lower, depending on how societies, including State, civil society, and market generate conditions for its inclusion. Nevertheless, we understand that the first guarantor of rights is always the State (Rossi & Moro, 2014). In consequence, we see disability as a situation that can be reduced if conditions are generated for all people to exert their rights, within the context of a society respectful of particular differences.

It is also important to observe that, although the analysis and results in this article are based on quantitative data, our study in all its components, including interpretation, discussion, and developing implications rely on our critical position. This, in an exercise of permanent reflection, and advocacy for generating better conditions so that people in a situation of disability can exert effectively their rights, in this case, to work.

Research Question and Hypotheses

The study addresses one research question:

1. How socio-demographic characteristics of people with disability increase the probability of being included in the labor system in Chile?

Associated to this question, the study tests the hypotheses presented below:

(a) Hypothesis 1: Being a woman in a situation of disability decreases the probability of participating in the labor system, in comparison to a man.

(b) Hypothesis 2: The higher the age of the person with disability, the probability of having a job is lower.

(c) Hypothesis 3: Living in a rural zone decreases the probability of participating in the labor system.

(d) Hypothesis 4: The higher the number of years of education of the person with disability, the probability of having a job is higher.

(e) Hypothesis 5: The higher the level of functional dependency of the person with disability, the probability of having a remunerated work is lower.

Theoretical Perspective

This study draws on the heterodox position and the legal framework based on the human rights approach to address the research question.

The heterodox position in economics has contributions from Marxists and feminist theories. From this perspective, labor discrimination is a tool of social control and domination: it supports dominant groups, while excludes ethnic and racial groups. To heterodox economists, labor exclusion is not a one-dimension phenomenon, but multifactorial. Material and historical conditions are also important components of the labor market experience, and they must be taken into account in such analyses (Ruwanpura, 2008).

In turn, the legal framework based on the human rights approach (Bell, 2016; Makkonen, 2002; Ruwanpura, 2008), considers that individuals can fit into several disadvantaged groups simultaneously; therefore, they can be discriminated against in multiple ways (Makkonen, 2002). It implies that discrimination can be direct (the person is treated differently on the basis of a prohibited ground), indirect (a neutral practice led a group to an adverse situation), or institutional (social structures produce discriminatory effects). Besides, discrimination translates into prejudices and attitudes that manifest in discriminatory behaviors. In other words, there would be a causal relationship between the opinions and feelings of people and the manifested action against other groups. To some authors, discriminatory behavior is a continuum between the production of stigmas and the acceptability (or unacceptability) of those stigmas (Arteaga & Montes, 2006).

In this vein, to Makkonen (2002), the category of disability is socially constructed, “what constitutes an impairment or disability […] has been understood and defined differently at different times and places” (p. 3). Thus, attitudes to labor inclusion of people in a situation of disability would be socially constructed based on different elements, possibly connected to a particular health diagnosis and beliefs associated with them.

Makkonen (2002) also presents the term intersectional discrimination. This is an encompassing concept that includes multiple-discrimination (i.e., the one that takes place on one attribute at a time, but with cumulative effects over time, most used in human rights) and compound discrimination (i.e., that takes place on two or more traits that add each other) (Makkonen, 2002). Intersectional discrimination implies an interaction between several forms of discrimination that operates in a specific and concurrent way. For instance, an indigenous woman with a disability may confront particular forms of discrimination because of the interaction of all of her particular traits. All of these discrimination strains have pervasive and (sometimes) invisible effects on the labor market and act in an overlapping manner (i.e., they stack in different times and contexts).

Some of the most referred variables used in research for discrimination in the labor market has been, among others, education (Barea & Monzón, 2008; Birau et al., 2019; Quiñones & Rodríguez, 2015; Silva et al., 2019), sex (and gender) (Barea & Monzón, 2008; Birau et al., 2019; Brown & Moloney, 2019; Coleman et al., 2013), and rurality (Mitra & Sambamoorthi, 2008; Rodríguez, 2009). In addition, type and severity of disability (Barea & Monzón, 2008; Brown & Moloney, 2019), sexual orientation, trade union membership (International Labour Office, 2003), and age (Birau et al., 2019; Coleman et al., 2013) has been mentioned.

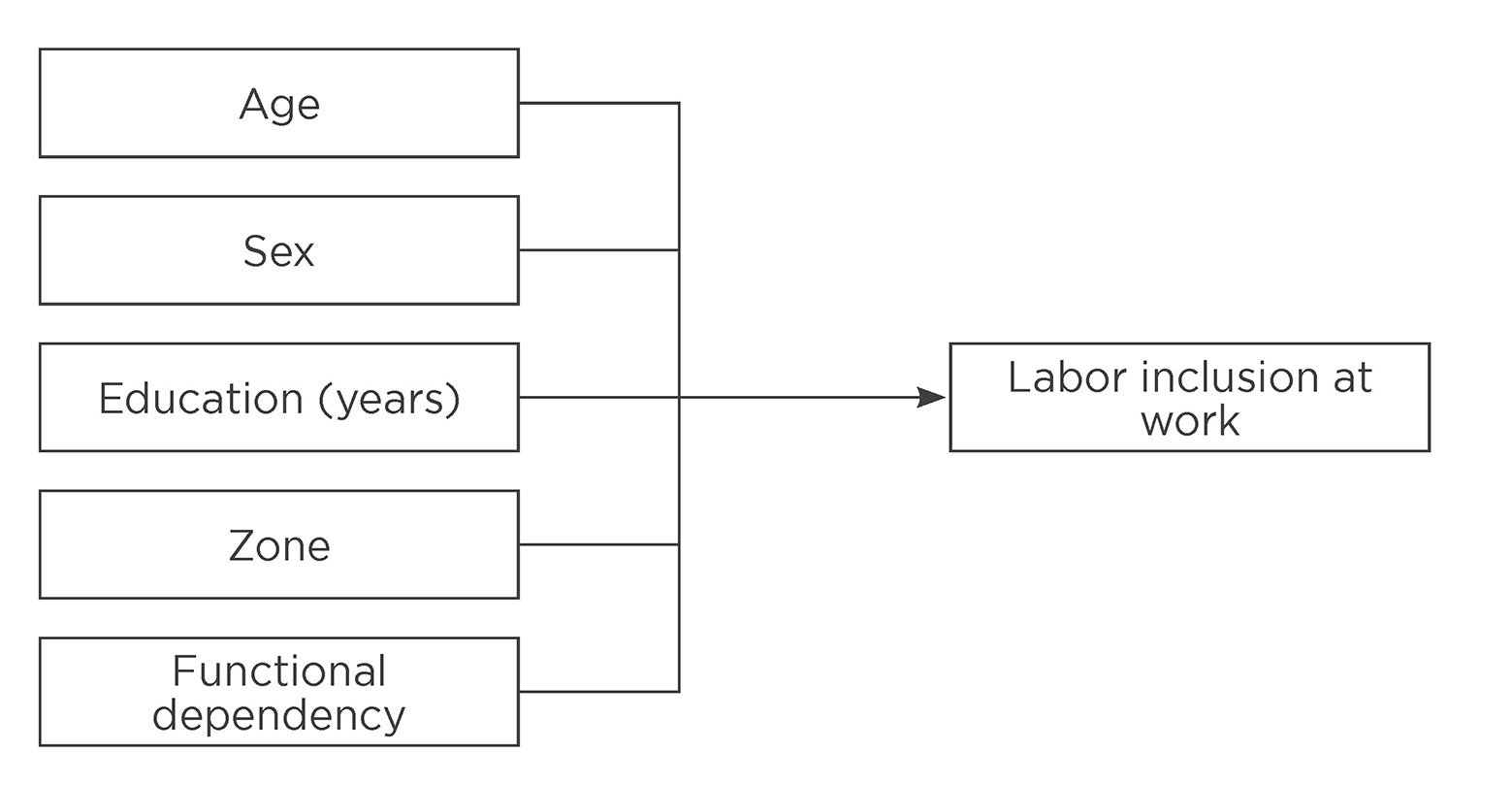

Taking the reviewed contributions, this study employs the variables used by these theoretical perspectives to develop a model (Figure 1), which may be helpful to inform the research question and hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model

Methods and Materials

Description of the Data

The scope of this quantitative study is explanatory. It bases on secondary data analysis. It uses the dataset of the Second National Survey of Disability in Chile (2016). The survey employed a representative sample of the general population. The target population of the survey was adults and children. Only adults in the situation of disability were included in this study (N=2,618). The representativeness in adults is at the national level, urban national, rural national, and at the 15 Chilean regions (Servicio Nacional de la Discapacidad, 2016) at that time.

The survey collected information on people in the situation of disability and no disability, on their work situation, and their sociodemographic characteristics, among other aspects.

Variables in the Study

The variables in this study relate to the theoretical perspective previously exposed. First, the dependent variable is “work” (having worked the week before at least one hour). It has two answer categories (1=Yes; 2=No). Second, the analysis includes three independent categorical variables: 1) sex of the person with a disability (a nominal variable with two categories, 1=Man and 2=Woman); 2) the zone in which the person lives (a nominal variable, with two categories 1=Urban; 2=Rural), 3) and the level of functional dependence (an ordinal variable with four categories, 0= No dependence; 1= Mild dependence; 2=Moderate dependence, and 3=Severe dependence). Besides, we included two interval independent variables: 1) the age in years old of the adult in the situation of disability, and 2) the years of education. With this variables selection, we shaped a parsimonious model to answer the research question.

Analysis

A binary logistic regression was performed to evaluate the scope of the stated hypotheses. Coefficients and odds ratios were calculated. All procedures (i.e., data management, data screening, and analysis of results) were conducted in STATA v.15.0.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Regarding descriptive statistics, the survey collected information about 2,618 adults with a disability. From them, 31.86% worked at least one hour the previous week, while 68.14% of participants did not. Regarding sex, 30.67% are men, while 69.33% are women. Their average age is 59.50, with a standard deviation of 17.98. The adult with a disability with the highest age is 107 years old, while the youngest is 18. The average years of education of persons with disabilities are 8.37, with a standard deviation of 4.72. Some individuals report zero years of education while there are individuals with 24 years. About the level of functional dependence, 62.07% are people that, presenting a disability, do not present functional dependence. In turn, 23.91% of them present a severe functional dependence, 9.09% mild dependence, and 4.93% moderate dependence. The mentioned statistics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of variables used in the study

|

Variables |

Percentage |

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

|

Worka |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

31.86 |

|

|

|

|

|

No |

68.14 |

|

|

|

|

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Man |

30.67 |

|

|

|

|

|

Woman |

69.33 |

|

|

|

|

|

Zone |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Urban |

83.31 |

|

|

|

|

|

Rural |

16.69 |

|

|

|

|

|

Functional |

|

|

|

|

|

|

No dependence |

62.07 |

|

|

|

|

|

Mild dependence |

9.09 |

|

|

|

|

|

Moderate dependence |

4.93 |

|

|

|

|

|

Severe dependence |

23.91 |

|

|

|

|

|

Age |

|

59.50 |

17.98 |

18 |

107 |

|

Years of education |

|

8.37 |

4.72 |

0 |

24 |

- Note: a) Dependent variable

Logistic Regression Analysis Results

Concerning the logistic regression analysis, almost all coefficients are statistically significant, except the one related to the zone in which the person with disability lives (rural or urban). Also, with exception of the years of education, all the coefficients present a negative relation with the probability of the person who can access a job. In other terms, increments in age, the fact to be a woman, living in a rural zone, and having a higher level of dependency decrease the probability of accessing the labor system. On the contrary, when the years of education increase, the probability to be included in the work system increase, too.

Regarding the interpretations of chances of occurrence, and based on the results of exponential betas (odds ratio), it can be mentioned that when the age increases in one unit, the odds of working decrease 4.1% (ceteris paribus the rest of the variables). Also, being a woman with a disability decreases by 44.5% the chances to get a job, in comparison to being a man (ceteris paribus). Also, when the year of additional education increases in one year, the chance of work increases by 6.8%, when controlling for the rest of the variables. Additionally, when the person lives in a rural zone, her or his chance to access to labor system decreases by 23.4%, in comparison to those, having a disability, live in an urban territory (again, all the rest constant). Finally, a person with moderate dependence faces a decrease of 85.1% in her/his chances of having work, in comparison to a person with a disability but no dependence. All previous results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Logistic regression results

|

Work (Yes) |

Model |

||||

|

Coeff. |

Coeff. |

Z |

Odds ratio |

95% CI (coeff) |

|

|

Age |

-0.04* |

0.00 |

-13.45 |

0.96 |

-0.05; -0.04 |

|

Sex (woman) a |

-0.59* |

0.10 |

-5.72 |

0.56 |

-0.79; -0.39 |

|

Years of education |

0.06* |

0.01 |

5.73 |

1.07 |

0.04; 0.09 |

|

Zone (rural) b |

-0.27 |

0.14 |

-1.89 |

0.77 |

-0.54; 0.01 |

|

Functional |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mild |

-1.42* |

0.21 |

-6.83 |

0.24 |

-1.82; -1.01 |

|

Moderate |

-1.90* |

0.34 |

-5.64 |

0.15 |

-2.56; -1.24 |

|

Severe |

-1.34* |

0.14 |

-9.76 |

0.26 |

-1.61; -1.07 |

|

Constant |

1.89* |

0.25 |

7.53 |

6.63 |

1.40; 2.38 |

|

|

|

||||

|

N |

2,616 |

||||

|

LR chi2 |

662.73 |

||||

|

P |

0.0000 |

||||

|

Pseudo R2 |

0.20 |

||||

- Note: Reference category is a) “man”, b) “urban”, c) “no dependence” *) p<.05.

Conclusions and implications for critical social policies

This paper sought to answer how socio-demographic characteristics of people with disabilities increase the probability of being included in the labor system in Chile. In this context, all the tested variables in the model show a statistical relationship and incidence in the probability of inclusion in the work system, with the exception of the zone in which lives the person.

Regarding assessed hypotheses, findings support hypotheses 1, and 2: being a woman in the situation of disability and having a higher age decrease the probability of participating in the work system. Also, findings support hypothesis 4: having more years of education increases the probability of work. These findings are supported by the extant literature (Barea & Monzón, 2008; Birau et al., 2019; Coleman et al., 2013; Garrido-Cumbrera & Chacón-García, 2018; Green & Vice, 2017; Pereda et al., 2003). Results also support hypothesis 5, namely, a person with a disability presents a severe dependence her or his probability of having a work decreases (in comparison to a person with no dependence). This agrees with previous research (Barea & Monzón, 2008; Brown & Moloney, 2019).

Findings do not support hypothesis 3, which is related with what literature suggests (Mitra & Sambamoorthi, 2008; Rodríguez, 2009).

Concerning theoretical premises, findings support the legal framework based on the human rights approach (Bell, 2016; Makkonen, 2002; Ruwanpura, 2008), where individuals suffer multiple discriminations due to the different membership in disadvantaged groups they are. In this vein, institutional discrimination, which is related to social structures, points towards the systematic effects (e.g., those by age and gender) observed here.

These multiple discriminations seem to intersect in what Makkonen (2002) states as compound discrimination, which would take place on two or more traits that add and act simultaneously.

Different implications for critical social policies are based on the findings of this study. First, promoting changes at the structural level is crucial towards active participation in the work system of people with a diagnosis connected to disability. In this vein, driving changes at the state policies with stability and permanency among administrations, as well as the engagement of the different state powers (Lahera, 2004) is paramount in order to promote changes with regard to how developing more inclusive societies that recognize and appreciate specific characteristics of every single person, including those in the situation of disability.

The country needs to promote, generate, and reinforce conditions to make sustainable these kinds of changes in the institutional design. This means not exclusively generating workplaces for people in a targeted way due to their health diagnosis. Neither this mean only to generate and reinforce mechanisms that make it easier to undertake businesses of people with a disability. Above all, this supposes generate conditions for exercising rights, including the one to work, in equal for everyone.

In doing so, from the critical perspective that this research takes, modifications at the institutional level require as an ethical imperative being conducted with the people in the situation of disabilities. Not including them in a binding way, would reproduce exclusion practices that have put them, as the results of this research shows, in a disadvantageous position.

In turn, improving institutional arrangements for increasing audit mechanisms to public and private sectors regarding how they promote and secure the inclusion into the work system is critical. In this sense, having the possibility to denounce eventual discrimination due to a health diagnosis linked to the disability situation is relevant. In this vein, restitution of the workplace and economic compensation is crucial. It would be just a nominal measure to have the possibility of just generating denounces. Sanctions should be the highest, including economic retributions to people with disabilities in order to decrease any possibility of arbitrary discrimination due to a health diagnosis or condition. Thus, providing institutional support to people with disabilities for reparation is imperative in these cases. Also, increase the power of trade unions is crucial in order to promote and secure their inclusion when people with disabilities are already included in the labor system.

Moving forward to inclusive and effectively guarantor systems of rights require that society as a whole, starting with the State, recognize and secure possibilities to carry out projects of life that include the exercise of the right to work in consonance with the particular interests and motivations of every single person, including those with a diagnosis traditionally related to disability.

Limitations

The scope of working with secondary data limits the inclusion in the analysis of variables related to specifics elements. Probably, producing primary quantitative data with tailored questionnaires would help to incorporate other key variables in the analysis of inclusion into the work system.

Despite this limitation, this paper provides evidence and a theoretical framework and model to highlight how specific variables would increase or decrease the probabilities of a person with a disability having a job, in the Chilean context.

References

Álvarez, P. (2012). Políticas públicas de inserción y mantención en el mercado laboral de personas con discapacidad intelectual: factores de incidencia en Chile. Universidad de Chile.

Andrade-Guzmán, C., Martínez, A., Arancibia, S., Molina, V. & Meseguer, M. (2014). Aprendizajes para las políticas e intervenciones sociales de discapacidad mental. El caso del Servicio de Capacitación Cecap, Toledo, España. Revista Gerencia y Politicas de Salud, 13(27), 90–121. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.rgyps13-27.apis

Arteaga, N. & Montes, C. (2006). Las fronteras de la violencia cultural: Del estigma tolerable al estigma intolerable. Convergencia, 13(41), 65–86.

Barea, J. & Monzón, J. (2008). Economía social e inserción laboral de las personas con discapacidad en el País Vasco. https://www.fbbva.es/publicaciones/economia-social-e-insercion-laboral-de-las-personas-con-discapacidad-en-el-pais-vasco/

Bell, M. (2016). Mental health, law, and creating inclusive workplaces. Current Legal Problems, 69(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/clp/cuw001

Birau, F. R., Dănăcică, D. E. & Spulbar, C. M. (2019). Social exclusion and labor market integration of people with disabilities. A case study for Romania. Sustainability, 11(18), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11185014

Brown, R. L. & Moloney, M. E. (2019). Intersectionality, Work, and Well-Being: The Effects of Gender and Disability. Gender and Society, 33(1), 94–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243218800636

Coleman, N., Sykes, W. & Groom, C. (2013). Barriers to Employment and Unfair Treatment at Work: A Quantitative Analysis of Disabled People’s Experiences. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/publication-download/research-report-88-barriers-employment-and-unfair-treatment-work-quantitative

Convención sobre los derechos de las personas con discapacidad. (2006).

Gallegos, F. (2019). Realidad tras el Desempleo de las Personas con Discapacidad, en la Ciudad de Guayaquil-Ecuador. Yachana. Revista Científica, 8(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1234/ych.v8i3.613

Garrido-Cumbrera, M. & Chacón-García, J. (2018). Assessing the Impact of the 2008 Financial Crisis on the Labor Force, Employment, and Wages of Persons with Disabilities in Spain. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 29(3), 178–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207318776437

Green, S. E. & Vice, B. (2017). Disability and community life: Mediating effects of work, social inclusion, and economic disadvantage in the relationship between disability and subjective well-being. In B. M. Altman (Ed.), Factors in Studying Employment for Persons with Disability : How the Picture Can Change (pp. 225–246). Emerald Publishing.

Guba, E. & Lincoln, I. (2005). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In N. Denzin & I. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 191–215). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

International Labour Office. (2003). Time for equality at work. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_publ_9221128717_en.pdf

Lahera, E. (2004). Política y políticas públicas. Naciones Unidas.

Lindsay, S., Cagliostro, E. & Carafa, G. (2018). A systematic review of workplace disclosure and accommodation requests among youth and young adults with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(25), 2971–2986. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1363824

Makkonen, T. (2002). Multiple, Compound and Intersectional Discrimination: Bringing the Experiences of the Most Marginalised to the Fore (Issue AprilMultiple, Compound and Intersectional Discrimination: Bringing the Experiences of the Most Marginalised to the Fore). http://web.abo.fi/instut/imr/publications/publications_online.htm

Martínez, B. (2011). Pobreza, discapacidad y derechos humanos. Aproximación a los costes extraordinarios de la discapacidad y su contribución a la pobreza desde un enfoque basado en los derechos humanos. CERMI.

Mitra, S. & Sambamoorthi, U. (2008). Disability and the Rural Labor Market in India: Evidence for Males in Tamil Nadu. World Development, 36(5), 934–952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.04.022

Ordóñez, C. (2011). Breve análisis de la inserción laboral de personas con discapacidad en el Ecuador. Alteridad, 6(2), 145–147.

https://doi.org/10.17163/alt.v6n2.2011.06

Palacios, A. (2008). El modelo social de discapacidad: orígenes , caracterización y plasmación en la Convención Internacional sobre los Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad. CERMI.

Pereda, C., DePrada, M. & Actis, W. (2003). La inserción laboral de las personas con discapacidades. https://sid.usal.es/libros/discapacidad/6641/8-1/la-insercion-laboral-de-las-personas-con-discapacidades.aspx

Pérez, G. (1994). Investigación cualitativa. Retos e interrogantes. La Muralla. Madrid.

Quiñones, S. & Rodríguez, C. (2015). La inclusión laboral de las personas con discapacidad. Foro Jurídico, (14), 32–41.

http://revistas.pucp.edu.pe/index.php/forojuridico/article/view/13747

Rodríguez, L. (2009). Yo trabajo, tu trabajas… y ¿ellos trabajan? Factores contextuales que inciden en la inclusión laboral de adultos en situación de discapacidad en el ámbito rural. Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Rossi, J. & Moro, J. (2014). Ganar derechos. Lineamientos para la formulación de políticas públicas. Instituto de Políticas Públicas en Derechos Humanos del MERCOSUR, IPPDH.

Ruwanpura, K. N. (2008). Multiple identities, multiple-discrimination: A critical review. Feminist Economics, 14(3), 77–105.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13545700802035659

Servicio Nacional de la Discapacidad. (2016). II Estudio Nacional de la Discapacidad 2015.

Silva, M., Mieto, G. & Oliveira, V. (2019). Recent Studies on Labor Inclusion of People with Intellectual Disabilities. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, 25(3), 469-486. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1413-65382519000300008

- 1 Doctor (c) en Trabajo Social, Universidad Alberto Hurtado, Chile y PhD (c) in Social Welfare, Boston College, Estados Unidos. Académico e investigador del Departamento de Trabajo Social de la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad Alberto Hurtado. Almirante Barroso, 10. Santiago de Chile. Código postal 8340575. Correo electrónico: caandrade@uahurtado.cl

- 2 Doctor en Bienestar Social por la Universidad Iberoamericana Ciudad de México y Boston College. Profesor en la Universidad Loyola del Pacífico, Acapulco, México. Correo electrónico: javier.reyes.academia@gmail.com

- 3 Postdoctorado Universitat de Barcelona, Doctora en Antropología Social, Universidad de Manchester, Reino Unido, Master en Antropología y Desarrollo, Universidad de Chile, Licenciatura en Trabajo Social, Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana, Académica Asociada Departamento de Trabajo Social, Facultad de Humanidades y Tecnologías de la Comunicación Social; Programa Institucional de Fomento a la Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación; Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana, Dieciocho 161, código Postal 8330378, Santiago de Chile. Correo electrónico: lvalencia@utem.cl